|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This 1998 photo shows the Tappan Zee Bridge from the Westchester shoreline in Tarrytown. Although it spanned the Hudson River at its widest point, the bridge was situated to take advantage of the developing metropolitan highway network. (Photo by Steve Anderson.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

WHAT IS THE TAPPAN ZEE? The name of the Tappan Zee Bridge was derived from Indian and Dutch origins. In pre-colonial days, the Tappan Indian tribe inhabited the area. When the Dutch inhabited New York in the 1600's, the Hudson River was called a "zee," or wide expanse of water. In 1994, the bridge was re-dedicated in honor of Malcolm Wilson, who served as governor of New York State in 1974 and 1975, and for nearly 15 years before that as lieutenant governor under Nelson Rockefeller.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THE NEED FOR THE TAPPAN ZEE BRIDGE: Plans for a trans-Hudson crossing from Westchester County had first arisen in the 1920's. The trans-Hudson bridge was proposed in conjunction with a circumferential highway that would encircle the New York-New Jersey metropolitan area. After spending many years in limbo, the circumferential highway plan was given serious consideration in the years after World War II, which saw unprecedented demands on the regional highway system.

In 1949, the New York State Thruway Authority (NYSTA) established as its goal the development of a toll superhighway connecting the major cities of New York State. Originally proposed to end in Suffern, Rockland County, the mainline route was extended into New York City after engineering and fiscal experts agreed that the extension would serve as an integral part of the system.

Earlier bridge plans called a crossing between Dobbs Ferry, Westchester County and Piermont, Rockland County (near Tallman Mountain State Park). However, the proposed Dobbs Ferry-Piermont location fell within the 25-mile radius of the Port Authority, which held jurisdictional rights to Hudson River crossings within its jurisdiction. The challenging geography of the lower Rockland County palisades also would have made construction of a connecting east-west roadway difficult.

In 1951, the proposed bridge was relocated to the current Tarrytown-to-Nyack location, incorporating the proposed Thruway extension between Suffern and New York City. This route would connect to (and take maximum advantage of) north-south arteries on both sides of the Hudson River, not only those in Westchester and Rockland counties, but also those existing or under construction in New York City, Connecticut and New Jersey. It also took advantage of the proposed route of the Cross Westchester Expressway (along the Central Westchester Parkway right-of-way), which was to comprise part of the metropolitan beltway

In June 1951, not long after the route of the span had been approved, workers drove the initial test pilings. Construction of the Tappan Zee Bridge, which was delayed by steel shortages brought about by the Korean War, began in March 1952. The engineering firm Madigan-Hyland oversaw construction.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Work on the Tappan Zee Bridge proceeds in these 1953 photos. (Photos from "This Is Westchester" supplied by James Rumbarger.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

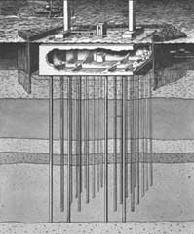

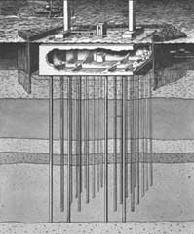

BUILDING THE FOUNDATIONS: Eight underwater concrete caissons, which support about 70 percent of the bridge's dead weight, are themselves supported by steel piles driven to rock. The caissons incorporate a "buoyant" design that stores pressurized air within small compartments. Water is periodically pumped out of these compartments, which range in number from 8 to 24 in each caisson, to achieve the desired buoyancy. This innovative design saved millions of dollars in construction costs.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The two largest caissons, which support the two main towers of the bridge, are 100 feet by 190 feet, and weigh 16,000 tons each. The two caissons for the flanking piers are 77 feet by 124.5 feet, and the four smallest caissons are 46 feet by 100 feet. Each caisson is 40 feet high, and has exterior walls that are 34 to 45 inches thick.

The caissons were constructed in a natural clay pit at Grassy Point, Rockland County, which is about 10 miles north of the bridge site. This pit, which is 32 feet below the river's surface at its deepest point, was the largest natural dry dock in the world. About 350,000 gallons of water were pumped out to permit construction of the caissons. All eight caissons were transported by barge to the bridge site, the first of which arrived on October 13, 1953.

Once the caissons arrived, they were floated into their exact position by maneuvering them into a fender system built for each pier. Open wells lined with corrugated, galvanized iron were run vertically through the compartmentalized walls of the caissons. The caissons were then filled with water and sunk atop a five-foot blanket of sand and gravel about 42 feet below the river surface.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Between Westchester and Rockland counties, the riverbed of the Hudson River consists of layers of silt hundreds of feet deep. With bedrock more than 300 feet below sea level, engineers found it difficult to lower the caissons. To solve this problem, they drove steel pipe piles, some up to 270 feet long, into the bedrock through the open wells of the caissons. Once the piles were driven, the pipe piles were cleaned out, filled with concrete and then encased by concrete within the walls to pin the caissons permanently in place.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

As construction of the bridge added dead weight to the caissons, water was pumped from them to obtain the desired buoyancy. Two pumps, a 60-gallon-per-minute pump for small amounts of water and a 300-gallon-per-minute pump for larger amounts, were installed at the low point of each caisson. These pumps continue to regulate the buoyancy of each caisson.

In addition to the 42,702 cubic yards of concrete, a total of 1,602,200 feet (303 miles) of timber piles, 330,500 feet (62.5 miles) of steel "H" pile and 33,400 feet (6.3 miles) of 30-inch steel pipe piles filled with concrete were used to construct the foundations.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

LEFT: Construction crews on the Tappan Zee Bridge meet midway on the cantilever span above the Hudson River in this 1955 photo. RIGHT: Diagram of a typical caisson on the Tappan Zee Bridge. To reach the bedrock more than 300 feet below the Hudson River, workers drove long concrete-filled steel piles from each foundation into the bedrock. (Photo and diagram by New York State Thruway Authority.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THE MAIN CANTILEVER SPAN: The original design of the Tappan Zee Bridge included a 1,112-foot steel tied-arch span for the main channel of the Hudson River. As construction progressed on the rest of the span, steel fabricators decided not to bid on the main span because their estimates exceeded that of the chief engineer. Subsequently, engineers selected a more economical cantilever design. The main cantilever span, which was to be 100 feet longer than the originally proposed main steel arch span, was to be the widest of its type.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Two steel falsework structures, each 16 stories high, were used to construct the main span and the two 293-foot-tall towers. Each falsework structure measured 517 feet long, 93 feet wide and 168 feet high. Derricks atop the falsework were used to build the main towers. Approximately 1,700 tons of steel were used for the falsework, which was constructed at Grassy Point and shipped by barge to the bridge site.

The derrick on each falsework had a 40-ton lifting capacity, and was used in erecting a 100-ton stiff-leg derrick on the main structure. The stiff-leg main structure derrick was used in the erection of the towers, the main span and the side spans.

The main cantilever span, which measures 1,212 feet in length, is comprised of cantilever spans of 340 feet and a suspended span of 531 feet. It is flanked by two 602-foot side spans.

THE DECK TRUSS SPANS: On either side of the main and side cantilever span are nineteen deck truss spans, each measuring 235 to 250 feet long, 93 feet wide and 28 feet deep. Each of the spans, which weighed as much as 900 tons, was shipped by barge from the Grassy Point assembly site, and hoisted into place by four 500-ton jacks. Two sets of falsework were constructed at Grassy Point to enable the workers at the bridge site to work without interruption. The falsework was returned to Grassy Point after each of the truss spans was delivered to the bridge site.

PIER PROTECTION: Until recently, all eight caissons are protected by an all-around pile fender system. During 2000, workers constructed a new pier protection system: the two main piers are now protected by a new, pre-cast concrete ring structure on steel pipe piles, while the flanking piers are now protected by a new, reinforced timber system designed to current standards. Concrete icebreakers, each of an equilateral, triangular hollow shape and measuring 90 to 110 feet long, are employed at each of the eight caissons. Icebreakers, which are of timber pile cluster construction, are used for the approaches.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This 1998 photo of the Tappan Zee Bridge was taken from the southeast angle in Tarrytown.Part of the New York State Thruway system, the Tappan Zee Bridge carries I-87 and I-287 across the Hudson River between Tarrytown and Nyack. Recent discussion has focused on its replacement by either a new bridge or by a tunnel. (Photo by Steve Anderson.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THE BRIDGE AND THE THRUWAY SYSTEM: On December 15, 1955, the Tappan Zee Bridge was completed as part of the New York State Thruway system, replacing the Tarrytown-Nyack ferry that existed previously. The $80.8 million bridge and its approaches required the relocation of 200 homes in Tarrytown and South Nyack.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Opened as part of the Suffern-to-Yonkers section of the Thruway, was designed to carry 100,000 vehicles on a peak day. During 1956, its first full year of operation, the bridge carried approximately 18,000 vehicles per day. That year, the bridge was included as part of the Interstate highway system. Originally designated I-387 for a brief period, the bridge was re-designated I-287 in 1958.

The Tappan Zee Bridge, whose main cantilever span remains the ninth longest in the world, now carries approximately 135,000 vehicles per day over its seven lanes. In recent years, the completion of the I-287 beltway around New York and New Jersey has placed heavy traffic demands on the Westchester-to-Rockland span. By 2025, approximately 175,000 vehicles are expected to cross the Tappan Zee Bridge each day.

When the bridge opened, tolls were collected in both directions. Today, tolls are collected only in the southbound / eastbound direction. In December 2003, the NYSTA opened two new 35 MPH EZ-Pass lanes to speed traffic through the Tarrytown toll plaza.

THE MOVABLE BARRIER SYSTEM: To maximize roadway efficiency, the seven-lane bridge utilizes a moveable concrete barrier. Tom Caruso of the NYSTA supplied the following information on the bridge's movable barrier system:

The seven-lane Tappan Zee Bridge, which currently employs a movable barrier system, converted in 1992 from a four-lane southbound, three-lane northbound configuration with Jersey barrier. Prior to 1987, the bridge had a three-lane northbound, three-lane southbound configuration, with a single-lane, wide-open, curb-height median strip.

Under normal circumstances, there are four southbound and three northbound lanes, separated by a jointed, moveable barrier. This configuration is switched from four-lane southbound, three-lane northbound to three-lane southbound, four-lane northbound each day around 2:00 PM for the afternoon rush, and then changed back later in the evening. Each changeover takes about 45 minutes.

The system used is from a company called Barrier Systems, and is similar to that used in a number of road construction sites, with the exception of the actual machine. Each three-foot-long section is made of concrete and is tied together by a metal hinge system. The cross-section of each section looks much like a jersey barrier, except for a "T"-shaped flare at the top. This flare is used by the barrier machine to pick up each section of the wall.

The Barrier Systems web site shows a big gangly orange machine that is typically used in construction, but on the Tappan Zee Bridge, there are three half-lane-width machines that are used two at a time in tandem to move the barrier. (Most likely, this setup causes less traffic congestion than using a single full-lane-width machine.) Moreover, these machines, which are painted "Thruway yellow and blue," are enclosed for all-weather use.

The first barrier machine starts at one end of the Tappan Zee Bridge, straddles the barrier in a channel that runs through the undercarriage on a curved diagonal, lifts it several inches, slides it over a few feet and sets it down in place. The second machine follows a few yards behind to complete the lane shift. On each machine, there are two operators at either end for steering. These operators follow guide markings painted on the pavement.

GOING PRIVATE? In January 2005, just one day after New Jersey acting Governor Richard Codey proposed either selling or leasing rights the state's toll roads to private investors, NYSDOT Commissioner Joseph Boardman hinted at selling the Thruway, or parts of the Thruway such as the Tappan Zee Bridge, to private investors. Governor George Pataki has not commented on this plan.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This 2002 photo shows the westbound (northbound) Tappan Zee Bridge approaching the main cantilever span. Note the "zipper barrier" in the center median. (Photo by Jim K. Georges.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A NEW TAPPAN ZEE BRIDGE? In April 2000, the engineering firm Vollmer Associates completed a three-year-long comprehensive study of the Tappan Zee Bridge and the I-287 corridor for the NYSTA, the New York State Department of Transportation (NYSDOT) and the Metro-North Railroad. The study determined that the following upgrades would be needed for the existing structure:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The bridge's original 6¾-inch-thick concrete deck should be replaced with a pre-cast panel deck that meets the modern 10-inch-thick standard. Thruway construction projects in the mid-1990's have already replaced the original deck along 20 percent of the bridge, mostly on the southbound (eastbound) lanes of the eastern deck truss. A second project to be completed in November 2002 will replace the deck on the northbound (westbound) lanes of the eastern deck truss, necessitating partial closures during off-peak hours. Still, approximately three-quarters of the original bridge deck has yet to be replaced.

The bridge should be strengthened to ensure its structural safety. Since the bridge opened, a seventh lane was added to handle growing traffic, and research has shown that the wind loads on the bridges are actually greater than the bridge was originally designed to handle. These increased load requirements have taxed the reserve strength built into the bridge. Additionally, studies have shown that the bridge is vulnerable to seismic activity.

Modern AASHTO-compliant pier protection (fender) systems should be constructed to protect the bridge's eight caisson-supported piers from boat collisions and ice flows on the Hudson River.

The causeway sections should be completed replaced. This project would consist of constructing a new deck, piers and supporting beams.

Finally, the entire length of the bridge should be seismically retrofitted. The report estimated that an earthquake registering between M5.0 and M6.0 could cause serious damage to the bridge, particularly on the causeway section.

In combination with traffic demand management (TDM) measures, rehabilitation of the existing Tappan Zee Bridge was estimated to cost $1.3 billion. However, this alternative neither increases vehicular capacity nor serves anticipated mass transit needs.

Instead, the Vollmer Associates study recommended a complete replacement of the existing span with a new eight-lane bridge. To accommodate the anticipated growth in reverse commuting, the bridge would have four permanent lanes in each direction. Moreover, the study explored the following mass transit options along the bridge and the I-287 corridor:

DEDICATED BUSWAY: connecting express bus stops at Suffern, Palisades Center, Tarrytown, White Plains (Westchester County Center) and Port Chester; estimated cost $2.0 billion.

LIGHT RAIL: connecting stations at Suffern, Palisades Center, Tarrytown, White Plains and Port Chester; estimated cost $2.6 billion.

COMMUTER RAIL: connecting stations at Suffern, Palisades Center, Tarrytown, White Plains and Port Chester; estimated cost $3.4 billion. This option would provide connections for a "one-seat ride" to New York City via the Metro-North Hudson Line, and changes for the New Haven, Harlem and Port Jervis lines. (A new extension of the rail line to Stewart Airport would bring the cost to $4.0 billion.)

Under all three options, improvements in roadway and interchange capacity would be made along the I-287 corridor. Specifically, the I-87 / I-287 interchange in Elmsford would be reconstructed, and I-287 would be expanded from six lanes to eight lanes (four in each direction) between the Garden State Parkway in Spring Valley and I-684 in White Plains. The NYSTA owns land on 150 feet of either side of the bridge for such roadway expansion.

Mark Kulewicz, director of traffic engineering and safety service at the Automobile Club of New York (the local affiliate of the AAA), advocated a new bridge as follows:

Instead of spending $1 billion to patch up a bridge that is already straining to handle the region's growing traffic volume, why not avoid all those years of messy construction delays and invest $4 billion in a modern structure that can serve more commuters, and in new ways?

For this new bridge - let's call it Tappan Zee II - would be no carbon copy of its predecessor. While the present bridge maintains seven lanes of traffic (including one center lane that switches directions for morning and afternoon rush hours with the aid of a moveable barrier), Tappan Zee II as envisioned would boast eight permanent lanes of traffic, four in each direction. And in the plan's most novel concept, the bridge's auto lanes would be flanked by tracks for a new commuter rail line that would run from Suffern in Rockland County to MTA-Metro North's New Haven tracks at the Port Chester station in Westchester County.

With a brand new eight-lane bridge and a new rail system to further ease auto traffic in a busy commuter corridor, why do we hesitate crossing over? First, we see a need to take a look at the larger Rockland-Westchester corridor to determine if the source of current commuter delays does not lie elsewhere, perhaps on the Cross Westchester Expressway (I-287), where interchange improvements are due to begin soon. Second, we would want some reassurance that the new rail line to be grafted onto the Tappan Zee II will attract a sufficient ridership to justify its cost. Is it possible that less costly projects - such as an exclusive bus lane on the bridge or the introduction of high-speed ferry service on the Hudson - offer better alternatives?

Not everyone agreed with the findings of the Vollmer study. Peter Samuel, editor of the Toll Roads newsletter, said that the findings were rigged against highway expansion and in favor of mass transit, citing the following:

Highway expansion was ruled out in this report by deploying blatantly stacked criteria in the alternatives analysis. The report was prepared for a Governor's Task Force led by MTA transit agency head Virgil Conway. The study rejected increased highway capacity - apart from the extra single bridge lane to allow fixed 2x4-lane operation in place of the present 4-lane-east / 3-lane-west AM, 3-lane-east / 4-lane-west operations - on the novel grounds that the increase in highway capacity would be "finite." The bizarre argument is made in this report that because extra capacity would be exhausted beyond 2020, there would be no "flexibility to handle traffic growth beyond 2020."

Variable pricing is rejected on the grounds that the peak is already heavily spread, due in part to the severity of peak congestion, so there is little '"shoulder'" capacity for pricing to exploit. Reverse commuting (westbound mornings, eastbound evenings) is growing so fast that reversible lanes will not work.

Finally, how transit-oriented are the people in this corridor? Despite years of subsidized transit it represents a mere three percent of trips to work. Yet despite the clear preference of the people of the corridor for car travel, the Conway task force did not set better car travel, or alleviation of road congestion as one of its goals. On the contrary, the first goal is to "decrease highway travel during weekday peak periods." The next goal is to "increase public transit use." The group was not even interested in catering to public needs as expressed by their travel preferences, but in manipulating a mode shift from road to rail transit.

The NYSTA is in the midst of a public information campaign as a prelude to the public hearing process. The agency presented 15 alternative designs for evaluation in December 2003 from more than 150 submitted, and subsequently subjected them to environmental studies. In September 2005, the NYSTA narrowed the list down to the following six alternatives:

ALTERNATIVE 1 ("NO BUILD"): The existing seven-lanes bridge would in maintained in its existing condition to avoid critical levels of deterioration. Estimated cost: $500 million to $700 million.

ALTERNATIVE 2 (REHABILITATION): This option would feature a complete rehabilitation and seismic retrofit of the span. Enhanced bus service and new park-and-ride lots also are part of this option, which is estimated to cost between $2.0 billion and $2.5 billion.

ALTERNATIVE 3 (NEW BRIDGE WITH BUS RAPID TRANSIT): This alternative would replace the existing bridge with a new span. The new span would feature eight general-use lanes, two bus rapid transit lanes that could be used for HO/T use (in which there would be a higher toll for single drivers), and breakdown shoulders. The HO/T lanes would run along I-287 (and I-87) from Suffern to Port Chester. Estimated cost: $5.0 billion to $6.5 billion.

ALTERNATIVE 4A (NEW BRIDGE WITH WESTCHESTER-ROCKLAND COMMUTER RAIL): The features of the new bridge are the same as in alternative 3, but would add a commuter (heavy) rail line from Suffern to Port Chester. Estimated cost: $11.5 billion to $14.5 billion.

ALTERNATIVE 4B (NEW BRIDGE WITH ROCKLAND COMMUTER RAIL AND WESTCHESTER LIGHT RAIL): The features of the new bridge are the same as in alternative 4, but would add a commuter (heavy) rail line from Suffern to Tarrytown, and a light rail line from Tarrytown to Port Chester. Estimated cost: $10.0 billion to $12.5 billion.

ALTERNATIVE 4B (NEW BRIDGE WITH ROCKLAND COMMUTER RAIL AND WESTCHESTER BUS RAPID TRANSIT): The features of the new bridge are the same as in alternative 4, but would add a commuter (heavy) rail line from Suffern to Tarrytown, and bus rapid transit lanes along I-287 from Tarrytown to Port Chester. Estimated cost: $9.0

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This 2002 photo shows the westbound (northbound) Tappan Zee Bridge along the long causeway section. (Photo by Jim K. Georges.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SHOULD THERE BE A NEW SUSPENSION BRIDGE? One proposal devised by URS Creative Imaging suggested building a dual-deck suspension bridge across the Hudson River that would carry 10 to 12 lanes of vehicular traffic, but would have no rail provision. The suspension bridge would be constructed parallel and to the north of the existing span, which would remain in continuous operation during construction.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The bridge itself would have a main span of approximately 3,000 feet, with side spans of approximately 1,000 feet. Suspender cables would support the western side span (as in a conventional suspension bridge), but the eastern side span would be supported by pile supports because the roadways would curve toward the existing approach before the main cables reach the anchorage. Two 500-foot-tall towers would support the main cables. However, it would be difficult to build anchorages in the silt-laden riverbed of the Hudson, leading some engineers to question the viability of a suspension bridge.

OR A NEW TUNNEL? In the October 2000 issue of Boating on the Hudson, environmental activist Alexander Saunders began his pitch for a tunnel across the current Tappan Zee site. Saunders' proposal has garnered the attention of environmentalists, transportation experts and regional planners. The "Tappan Tunnel" article stated the case for the tunnel as follows:

In the current social and economic context using current technology, tunneling provides significantly more economics, safety, less intrusiveness to the municipalities affected, and less disruption to continuing traffic. Modern tunneling equipment is reliable, efficient, safe and highly economical in its use of manpower. In addition to producing the needed transportation infrastructure, tunneling yields very valuable byproducts. The gravel produced by the excavation is readily marketed and in short supply. The real property currently under pavement has great value when returned to private use, which may include residential developments, industrial parks and municipal parks. The final cost of an underground highway and rail system will be significantly less than continued maintenance and enlargement of the current surface system.

The tunnel facility would consist of three 60-foot-diameter tubes, with three traffic lanes (and continuous emergency shoulders) constructed on the upper level of each of the three tubes, and two rail lines on the lower level of each of the tubes. Combined, the six rail lines would serve both commuter and freight traffic. An additional service tunnel may be constructed for maintenance and emergency usage.

To build the tunnel, one or more boring machines (each costing up to $50 million) would tunnel beneath the Hudson River. Each machine would have a "production rate" of up to 130 feet per day. The steel-and-concrete lined tubes would be burrowed through the soft sediments below the riverbed.

According to the RPA, an engineering analysis would be necessary to determine appropriate highway and rail grades. The existing maximum grade between Nyack and Tarrytown is 1.2 percent, well within the three-percent maximum for Interstate highway service, but just outside the one-percent maximum for rail service. A major drawback of this proposal would be that the tunnel would overshoot EXIT 9 (US 9) in Tarrytown and EXIT 10 (US 9W) in South Nyack.

Borrowing from tunneling breakthroughs achieved during the late 1990's in Europe, Saunders estimates that the Tappan Zee Tunnel would cost $700 million (not including the cost of approach highways), and be constructed within five years. He proposed that the Tappan Zee Tunnel be part of a long-range master plan to place the entire I-287 corridor - from Suffern, Rockland County to Syosset, Nassau County - in a combined road-and-rail tunnel.

THE NEW FAVORITE DESIGN: A CABLE-STAY SPAN: Toward the end of 2005, the cable-stay bridge option emerged as a favorite because it offers almost the same long-span and capacity capabilities of a suspension bridge option at a significantly lower cost. Moreover, a cable-stay span does not require the deep concrete anchorages necessary for suspension bridge construction.

REACHING CONSENSUS, BUT IS IT TOO AMBITIOUS? On September 25, 2008, officials from NYSDOT, NYSTA, and Metro-North agreed upon a proposal to build a new Tappan Zee Bridge that would accommodate vehicular, bus rapid transit (BRT), and commuter rail traffic (the so-called "Alternative 4B"). The bridge itself would cost $6.4 billion and after a design and environmental review period, currently is scheduled for construction between 2012 and 2017. Construction of a new $2.9 billion BRT corridor on I-287 between Suffern and Port Chester and a $6.7 billion heavy-rail corridor to connect Metro-North stations in Tarrytown and Suffern would be built at a later built. However, given the financially tumultuous environment in which the joint proposal was announced, it remains to be seen whether the 2012-to-2017 construction time frame could be met and the ancillary mass transit projects be built.

If built with a cable-stay design, the new Tappan Zee span likely would resemble the Oresund Bridge, which was built between 1996 and 2000 to connect Denmark with Sweden, but on a larger scale. The Oresund Bridge carries four lanes of highway traffic on its upper deck and two high-speed rail tracks on its lower deck, while the new Tappan Zee would carry eight lanes of vehicular traffic as well as a dual-track accommodation for heavy rail.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THE TAPPAN ZEE SUSPENSION BRIDGE: One alternative proposed for the Tappan Zee corridor calls for a dual-deck suspension bridge. At the present time, no alternative has been adopted officially, though a cable-stay alternative has emerged as the favorite. (Photo by URS Creative Imaging.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BUILD A NEW TAPPAN ZEE SUSPENSION BRIDGE: To cope with the projected 48 percent increase in traffic during the next 20 years, a new dual-deck, 12-lane suspension bridge and causeway should be built to replace the existing Tappan Zee Bridge. The second deck could be used for HOV and bus use only during peak periods (e.g., morning and afternoon rush, as well as summer weekends and holidays). The HOV and bus lanes would be extended east and west along I-287, providing a cost-effective mass transit alternative.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

WHAT OTHERS HAVE TO SAY: Douglas A. Willinger, frequent contributor to nycroads.com and former Westchester County resident, provided the following comments in misc.transport.road:

The new Tappan Zee crossing should have a minimum of eight vehicular lanes, plus provisions for commuter rail. Given that the new crossing would be expected to last at least for the next 50 years, and given the relative shortage of east-west capacity in Westchester County, such a crossing should be constructed with not only rail, but also additional highway lane capacity.

Since the I-287 beltway was completed through northern New Jersey in 1994, traffic has increased considered along the I-287 corridor through Westchester and Rockland counties. To remedy this congestion, a dual-carriageway setup (perhaps with four local lanes and two express lanes in each direction) would probably make sense. This arrangement would improve safety separating long-distance traffic from local traffic.

Chris Blaney, frequent contributor to nycroads.com and misc.transport.road, proposes a solution for adding capacity between Westchester and Rockland counties as follows:

For the suspension bridge option, the upper deck should have six lanes of traffic, and the lower deck six lanes. The upper deck would carry four lanes of fixed express traffic (two eastbound, two westbound), with a pair of reversible express lanes in the center that would carry an additional toll over and above the other express lanes during peak periods. All the express lanes would be available only to passenger cars and buses with EZ-Pass tags.

The lower deck would carry six lanes of local Tappan Zee Bridge traffic for trucks and non-EZ-Pass passenger cars and buses. It should be reversible so as to provide four eastbound lanes in the morning, and four westbound lanes in the evening, using a zipper barrier system as is used on the existing bridge.

The toll on the new Tappan Zee Bridge should be the same as that on the Port Authority trans-Hudson crossings. Using the central express lanes would cost the same as the cash toll, and be charged in both directions.

Approaching the new Tappan Zee Bridge, the New York State Thruway between Suffern and Tarrytown should go from its existing six-lane configuration (three lanes in each direction) to a nine-lane (3-3-3) configuration in which the three center lanes would be reversible. Under this design, six lanes would be provided eastbound (southbound), and three lanes would be provided westbound (northbound), during the morning rush hour. This configuration would be reversed during the afternoon rush hour. The reversible express lanes would have reduced toll and a speed limit of 65 MPH (as opposed to 55 MPH for the local lanes).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Type of bridge:

Construction started:

Opened to traffic:

Length of main cantilever span:

Length of side cantilever spans:

Length of bridge, main and side spans:

Number of secondary deck truss spans:

Length of secondary deck truss spans:

Total length of bridge and approaches:

Width of bridge:

Number of traffic lanes:

Clearance at center above mean high water:

Height of towers above mean high water:

Concrete used in eight caissons:

Concrete used in entire structure:

Reinforcing steel used in entire structure:

Structural steel used in entire structure:

Timber piles used in bridge foundations:

Cost of original structure:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cantilever and truss

March 16, 1952

December 15, 1955

1,212 feet

602 feet

2,416 feet

19 spans

235 feet to 250 feet

16,013 feet

90 feet

7 lanes

138.5 feet

293 feet

42,702 cubic yards

153,900 cubic yards

14,610 tons

59,250 tons

1,602,200 feet (303 miles)

$80,800,000

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SOURCES: Reports of the Westchester County Parks Commission (1926-1935), Westchester County Parks Commission (1935); "Let's Be Realistic About Thruways" by Hugh R. Pomeroy, Westchester County Planning Department (2/21/1950); "Statement on Navigation Aspects of the Proposed Nyack-Tarrytown Location for the New York State Thruway Crossings of the Hudson River" by Hugh R. Pomeroy, Westchester County Planning Department (1/04/1951); "Thruway Jumps the Hudson River to Yonkers" by Joseph C. Ingraham, The New York Times (12/04/1955); "A Guide to Civil Engineering Projects in and Around New York City," American Society of Civil Engineers (1997); "Tappan Zee Rehab Would Cost $1 Billion," The Bergen Record (1/07/2000); "Tappan Zee Rush Hour Toll Hike Planned" by Carl Campanile, New York Post (1/12/2000); "Tappan Zee: A Bridge Too Far Gone?" by Mark Kulewicz, Car and Travel-Automobile Club of New York (March 2000); "The Tappan Tunnel" by John H. Vargo, Boating on the Hudson (October 2000); "Final Report for Long-Term Needs Assessment and Alternative Analysis, I-287 / Tappan Zee Bridge Corridor," Vollmer Associates (2000); "Holland, Lincoln and Now: the Tappan Zee Tunnel?" by Judy Rife, The Times Herald-Record (1/24/2001); "Thruway Authority Pledges To Seek Out Public Opinion on Tappan Zee Bridge's Fate" by Randal C. Archibold, The New York Times (2/07/2001); "Further Explanation of Tappan Zee Options Sought" by Greg Clary, The Journal-News (5/17/2001); "Creating a New Gateway to NYC" by Cathy Woodruff, The Albany Times-Union (1/05/2003); "A Transportation Dreamer Follows His Inner Mole" by Matthew Purdys, The New York Times (1/05/2003); "Bridge Awaits a Makeover, or a Successor" by Barbara Whitaker, The New York Times (4/17/2004); "Want a Bridge? State Has Plenty" by Cathy Woodruff, The Albany Times-Union (1/26/2005); "Six Options for TZ Future" by Jorge Fitzgibbon and Bruce Golding, The Journal-News (9/30/2005); "Possibility Grows for New Cable-Stayed Span on the Hudson" by Richard Korman, Engineering News-Record (12/12/2005); "State To Replace, Not Rebuild, Tappan Zee Bridge" by William Neuman, The New York Times (9/26/2008); New York State Thruway Authority;; URS Creative Imaging; Chris Blaney; David Butlien; Tom Caruso; Rich Dean; Ralph Herman; Scott Kozel; Peter Samuel; Alexander Saunders; Christof Spieler; Stephen Summers; Stéphane Theroux; Douglas A. Willinger.

I-87, I-287, and New York State Thruway shields by Ralph Herman.

Lightposts by Millerbernd Manufacturing Company.

HOV lane sign by C.C. Slater.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site contents © by Eastern Roads. This is not an official site run by a government agency. Recommendations provided on this site are strictly those of the author and contributors, not of any government or corporate entity.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|